Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the book that started my love affair with literature and writing. I’m pretty sure Moms For Liberty (those do-gooders who are spearheading much of the book-banning nationally) would have ripped that book from the shelf of my youth and thrown it on the smut pile.

And if I’d never encountered that murder mystery with that salacious dollop of nudity, I would probably be selling life insurance or real estate and withering away in “quiet desperation” (Thoreau).

Was that librarian in her long blue and white flowered dress in that dusty library in Hopkinsville, Kentucky in the 50’s trying to groom me, seduce me into a life of licentiousness?

Hell, no. Like most librarians I’ve met over the years, her main goal was to foster a love of books and reading because I’m pretty sure she believed, as most other librarians do, that reading books, even mysteries and crime novels, was a reliable way to broaden the horizons of the patrons of her library and introduce them to a range of possibilities they might never have considered.

On her shelves were books whose values and perspectives challenged and enlightened and educated young readers. That was her simple and noble mission. Books that question the status quo, that provoke strong emotions, that force a reader to more deeply consider their own biases and lazy prejudices and intolerance, those are the books that truly enrich us as individuals and as a society.

Restricting the books on library shelves to those which fit the narrow-minded, self-righteous values of a few well-organized sanctimonious zealots could very well groom a generation to the same level of ignorance and intolerance as these Moms For Liberty.

I offer again the following essay–my love letter to libraries.

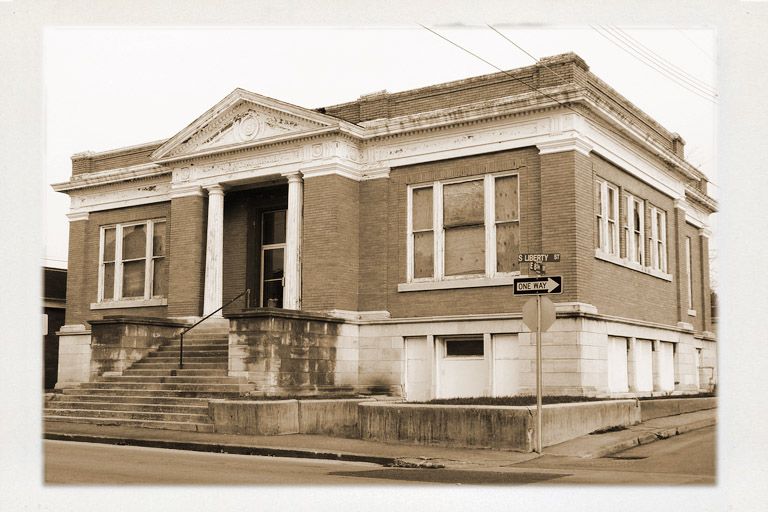

This is the library of my youth, fallen into disrepair.

This is a view of the ‘restored” library. To the right is the First Presbyterian Church where I spent Sundays as a kid.

NUDE WOMAN IN THE GRASS

My love affair with books began as most serious romances do, when I was least expecting to fall in love. I was ten years old, maybe eleven, and for years I had dutifully read the required books in school, but because they were required and because I was tested on my comprehension of them, I had decided that reading books ranked alongside long division and penmanship as simply one more bothersome educational duty.

Context is important here, for I was a young male in a southern town of the 1950s. In other words, that I would read a book just for fun was about as likely as my deciding spontaneously to knit a sweater for the football coach. It wasn’t done. At least not by any of the male role models who shaped my thinking at the time.

So when my mother deposited me at the public library that fall afternoon to get me out of her hair while she went about her downtown errands, she might as well have dropped me off in the middle of Death Valley The building was one of those structures built in the dreary style of many other Carnegie libaries of its era. That creaky battleship was piloted by a wispy, white-haired woman in a dark dress and thick glasses, a living cliché who floated noiselessly up and down the stacks replacing volumes in their proper slots and leaving the dry dust of tedium in her wake.

As a young boy who aspired only to muscular achievements on hash-marked fields or gymnasium floors, I was mortified. Frightened out of my skin that I would be spotted by one of my friends in such a place.

To make myself as invisible as possible I moseyed down aisle after aisle studying the titles of those musty tomes, bored to death by the prospect of spending an hour or two in that dismal room. When the passing librarian seemed to sense my discomfort and began to home in on me, a fit of panic spurred me to nab a random book from a shelf, pop it open to the first page, and feign deep interest.

As my eyes ran down the lines of print, I was suddenly breathless. Though my vocabulary was no larger than that of any average ten-year old boy of my place and time, I did know the word nude. It was one of those special, cherished words, not quite a curse, but nonetheless a word loaded with magical potency. And lo and behold that very word leaped out of the first page and seized my full attention. The fact that the word nude turned out to be an adjective modifying the word woman made my knees weak and put a wobble in my pulse.

I looked up, certain that the librarian was about to rip this smutty book from my hand, grab me by the collar, and toss me onto the street. By evening it would be all over town: “Little Jimmy Hall was caught reading that nude woman book in the library.” But magically, the librarian melted back into the stacks, and I was left alone with my first murder mystery novel.

For the nude woman was dead, and it was her corpse that had been found in a field by a man chasing butterflies. How did she get there? Who was she? Who would have done such a thing? I was mesmerized. Weak of breath and nearly fainting from a preadolescent tumult of emotions, I located a private corner near a window I looked around and planned my getaway should my mother suddenly reappear and find me reading that filth. Then I sped through as many pages as I could manage before she returned and called me away.

To my disappointment, there was no graphic description of the woman’s nudity, nor was there any further mention of her appearance in the tall grasses of that field. Nevertheless, I was hooked on the story—the exact condition its author must have hoped to inspire.

So this was why people read! Books were about adult things. Strong emotions, extreme behaviors, the inside stuff of a world I had never imagined existed. In this my first recreational book I suddenly realized that novels could fill one with heart-pounding fear as well as lip-smacking lust. That they could, in fact, suddenly expand the boundaries of the tiny backwater town where I had always lived and where I imagined I would always stay.

Tramping across the bogs of the English countryside in pursuit of the heinous killer of that nude woman, I was suddenly freed of my homebound life. I was set loose in the world and allowed to know every crucial thought of that droll British detective and was just as stumped as he, just as frustrated, and finally just as delighted when the logic of his deductions led him to the surprising culprit.

It took me several more surreptitious visits to the library to finish that novel. Surely my mother and father were deeply puzzled by this new enthusiasm, but they had the good grace not to ask where it was coming from. That might have quashed it all.

The day I finished that first novel, I looked up to find the amiable librarian staring down at me.

I gulped.

“You like mysteries?” she asked.

I gazed at the book in my hand as though it had just materialized there.

“Oh, this?”

“Yes, that. That book you’ve been reading these last few weeks.”

“I guess so,” I said.

“Well, so do I.” She beamed. “I just love a good murder story.”

And she gave me a conspiratorial look that still floats into my mind whenever I am feeling isolated from the human race. For as I have come to understand, reading is at once a private and a communal act. While books are savored alone, they grant you membership in the most fascinating club I know: fellow readers. Fellow voyagers into the vast uncharted waters of imaginative literature.

That afternoon the librarian gave me a private tour of that big dusty room and showed me the best mysteries in the house. Hard-boiled, cozies, Sherlock Holmes. She made a pile, got me a library card, helped me fill it out.

“Tell me what you think,” she said.

“Okay,” I said uncertainly.

“Oh, don’t worry, this isn’t school,” she said. “There’s no test when you bring them back. I won’t take your library card away from you if you don’t read one all the way through.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I don’t know if I’m smart enough to read all these.” I patted the stack of books.

“Oh, my,” she said. “No one starts out smart. That’s why we read.”

Over the next few years I gradually climbed onto the literary high road and read Dickens and Hardy and Joyce, and later I fell in love with Lawrence Durrell and John Fowles, Faulkner and Steinbeck, and the poets Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton and Robert Frost. It came as a shock to learn that sports and reading were not mutually exclusive. In fact, when I discovered Hemingway and began reading about his intense competitive exploits, I started to picture the unspeakable—that I might someday learn the craft of writing well enough to create the very things I so dearly loved to consume.

Though that creaky library has been restored almost beyond recognition, and though I have fled her narrow streets and scrubby fields forever, the largest part of what I am today and what I know about the world and about the affairs of the human heart springs from that one autumn afternoon when I plucked a book from the shelf and encountered that nude woman lying in the grass and I began this long journey, year after year, filling myself beyond the brim with the great accumulated wealth of books.

(This essay is taken from my collection Hot Damn!)

Dear Jim,

When the reader has had the very same experience that the writer, so eloquently described as his own, the world expands. I too grew up with a Carnegie library. The librarian graduated me to the adult mysteries when I had read the children’s mystery section. It was a coming of age experience no one else ever knew. I hold that experience in my memory as one of the best. My librarian launched me into the world, with the trust I would never stop. She made me believe I was more. Smarter. Stronger than I could ever imagine.

Thank you for sharing.

I miss you. What an experience to share your first major publishing!

Very moving. Was the book an Agatha Christie? what was the book?

Hey Glenn: It might have been. I don’t remember that. And I’ve not tried to track it down partly because I don’t want to be disappointed in what I might find.